Disposable Workers: Today’s Reserve Army of Labor

But if a surplus labouring population is a necessary product of accumulation or of the development of wealth on a capitalist basis, this surplus-population becomes, conversely, the lever of capitalistic accumulation, nay, a condition of existence of the capitalist mode of production. It forms a disposable industrial reserve army, that belongs to capital quite as absolutely as if the latter had bred it at its own cost.

—Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1

These are difficult times for workers. In the wealthy countries of capitalism’s center, labor is struggling to maintain existing wages and benefits against a combined assault by corporations and governments, while conditions of workers in the periphery are even more difficult. The widespread acceptance and adoption of capital’s agenda—”free trade,” “free markets,” greater “flexibility” regarding labor, and reduced social welfare assistance—has led to one group of real winners. Transnational corporations (and their owners and top managers) now have more freedom to produce where labor and other costs are cheap, have their patents protected, and move capital in and out of countries at will. Many workers, unfortunately, are finding that their situation has become more tenuous.

Many changes in the U.S. economy—including those leading to increased pressure on labor—can be traced to the period of the late 1970s and early 1980s (see “The New Face of Capitalism: Slow Growth, Excess Capital, and a Mountain of Debt,” April 2002 Monthly Review). These changes embody capital’s response to the stagnation that developed in the economies of the center following a period of rapid growth after the Second World War. In the absence of new technologies or other stimuli able to invigorate the economy, capital had an urgent need to find new ways to squeeze out more profits. The current U.S.-led drive to tear down international barriers to capital—commonly referred to as “globalization”—is nothing more than the aggressive search for new profitable investment opportunities abroad. The numerous limitations to foreign investment in the periphery provided one of the reasons for capital’s global offensive. A significant number of countries in the periphery, freed from colonialism after the Second World War (such as India), had created barriers and restrictions on foreign capital as part of their effort to develop independently.

Capital’s push to enhance the profitability of investments in the countries of the center has resulted in decreased job security and social benefits. While we will focus below on the United States, the situation in Europe is similar. For example, the trend toward privatization and the calculated policy to lessen union strength have beaten down the once powerful British labor movement. And in Germany, corporations and government—attempting to increase capital’s profitability—are changing the privileged position that labor has held since the Second World War. Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder boasted that “we have restructured the labor market to enhance its flexibility…With our radical reforms of the country’s social security systems, most notably health care, we have paved the way for the reduction of nonwage labor costs” (Wall Street Journal, December 30, 2003). In other words, German capital is weakening labor rights, making it easier to discharge workers, and at the same time reducing social benefits.

Government policies in the periphery, combined with the investment drive of international capital, have created very difficult conditions for labor in those countries. In China, laborers from the interior live in inadequate and overcrowded dormitories, work long hours for little pay, have no real unions, and have few, if any, rights. Workers trying to organize unions in Latin America are in constant danger (for example, organizers of workers at Coca-Cola bottling plants have been killed). In South Africa, the embrace of neoliberalism by the African National Congress-led government has left one of its partners and original backers, the trade union movement, demoralized. Privatization schemes and a variety of laws that harm workers have been put into place. While conditions have improved for some workers, such as computer programmers in India, the general situation of labor around the world is grim and appears to be getting more so.

In response to increasingly harsh conditions throughout capitalism’s periphery (including violence against farmers and the landless poor), people are on the move from the countryside to the overcrowded urban centers of the third world, which do not have sufficient jobs to absorb the newcomers. The result is a huge increase in the number of people living a hand-to-mouth existence in slums. These new recruits for the reserve armies of their countries are also available to international capital.

The overall goal of capital’s new course is enhanced profitability through greater flexibility on all fronts—to hire and fire workers, obtain low-cost labor, decrease worker and citizen benefits, invest and market abroad, repatriate profits, and gain access to needed raw materials. These efforts to improve the profitability of investments at home and abroad, have resulted in greater numbers of workers living under insecure conditions. However, the presence of a large pool of workers living a precarious existence is nothing new. It is one of the basic characteristics of capitalism, referred to by Marx as the reserve army of labor. More than an underlying attribute of capitalism, the reserve army helps to keep costs down—permitting the market system to function profitably—and serves as a constant and effective weapon against workers.

The Reserve Army of Labor

One of the central features of capitalism is the oversupply of labor, a large mass of people that enter and leave the labor force according to the needs of capital. During an upswing in the business cycle, additional labor is necessary to utilize a business’s full capacity. As sales slacken during a recession, workers no longer needed are then dismissed. The reserve army of labor—with brief and very unusual exceptions—is always present. Under the exceptional conditions of the Second World War, there was full employment in the United States because it was necessary to expand the labor supply for the war effort. This was accomplished partially by bringing large numbers of women into the labor force. Full employment was reached at a time when 11 million people were in the armed forces and thus not part of the labor force.

When considering the surplus of workers in the reserve army of labor, it is important constantly to keep in mind two points. First, there is not an absolute surplus population, but rather a surplus in the context of a society ruled by the profit motive and the golden rule of accumulation for the sake of accumulation. Second, there would be no surplus of labor if everyone had enough to eat, a decent place to live, health care, and education, and workers had shorter work hours and longer vacations so they could have more leisure and creative time.

Business owners or CEOs protect and maintain the structural and mechanical parts of their operations, even when not fully utilized (or not used at all) because of insufficient demand. Capitalists take care of their buildings—factories, offices, and stores—and the various pieces of machinery and equipment are usually serviced and maintained regardless of business conditions. Workers, on the other hand, are disposable. Capital wants to obtain labor and use it when needed, and layoff workers when they aren’t needed. Treating labor as a disposable and/or easily replaceable part of the production process promotes capitalism’s central driving force—the never-ending drive to accumulate wealth. It is of critical importance to the functioning of capitalism as a system because it enables individual capitalists to change course quickly in response to changing economic conditions.

What economic sense could it make for a capitalist to pay a workforce to do little or no work during a recession? What business sense would it make for a farmer to pay a person year-round when all that’s needed is extra labor during a short harvest period? The argument could be made that there are certain individuals that have key skills and employers would be well served by paying these persons through a slack period to insure that they would be available when demand for the product or service begins to grow again. To some extent this happens, but the reserve army also includes technical workers—computer scientists, engineers, and technicians—so it is possible to find ready replacements for many seemingly irreplaceable workers.

Members of the reserve army—a mass of people living in insecurity or fearful of future job prospects—can be thought of as belonging to one of the following broad categories:

the unemployed (including those officially recognized as unemployed because they have recently looked for work as well as those that have stopped looking because they can’t find jobs);

part-time workers that want to work full-time;

people making money independently (self-employed) doing various odd jobs or getting occasional work while desiring a full-time job;

workers in jobs that are likely to be lost soon (due to economic downturn, increased mechanization, or their jobs moving to countries where workers earn lower wages). Although not unemployed, these workers usually know that they are in a precarious situation and behave accordingly. Agricultural labor displaced by increased productivity in the countries of capitalism’s center no longer provides large numbers of reserve army members. However, people displaced from agriculture in the periphery are a huge potential source of reserve labor for their own countries and, as immigrants, for the center;

those not counted among the economically active population but available for employment under changed circumstances (such as prisoners and the disabled).

Through much of U.S. history, employers had the right to terminate employment at will. As far as capital is concerned, this is the most desirable situation because it provides the highest level of flexibility to control labor and labor costs. The wording of an 1884 Tennessee Supreme Court decision is an indication of the extent of capital’s rights during this period:

Men must be left, without interference to buy and sell where they please, and to discharge or retain employees at-will for good cause or for no cause, or even for bad cause without thereby being guilty of an unlawful act per se. (Payne v. Western & Atlantic Railroad, Tennessee 1884)

The doctrine of firing workers at will applied to most workers, except where union contracts stipulated otherwise. However, legislation at the state level and legal findings in state courts gradually modified this right of capital for many states. This made it more expensive to fire workers with implied contractual rights to continued employment—when not done for reasons of financial need—often resulting in lengthy legal battles and/or severance pay. Capital has responded with techniques to overcome this handicap such as increased use of temporary, part-time, and contract labor, the privatization of government functions, and outsourcing portions of industrial and service operations to other locations at home and abroad. All of these contingent or nonstandard work arrangements have the advantage for capital that they further weaken its already weak obligations to workers.

The Supply of Workers for the Reserve Army

The reserve army has not remained the same over the years. The details of its composition and sources of supply have varied through history, according to local conditions and the economic relations between the countries of capitalism’s center and periphery. The supply of people for the reserve army is generally provided through the normal workings of capitalist development—job growth is rarely great enough to keep pace with both population growth and the employment needed for those workers displaced by increased labor productivity. Sometimes land is taken for development—for dams, roads, and factories—forcing displaced farmers to seek employment in cities. Productivity growth, the mantra of many academic economists, is supposedly good for both capital and labor. It is maintained that as productivity increases, higher wages for workers are possible while at the same time higher profits can go to owners of capital. However, the reality of increasing labor productivity under capitalism usually has been quite different.

Using new technologies to increase production with less labor, early capitalist management of agriculture in Western Europe became more profitable than relying on rents paid by tenant farmers. Tenants and laborers were forced off the land, expanding the number of those who had no alternative but to sell their labor power and participate in the huge migration to cities during the initial growth of capitalism. During early stages of its development, the United States had no such internally available reserve of labor. Before the mid 19th century most of the new immigrants from Europe became farmers and craftspeople. With little industrial development, there was no need for a sizable reserve army. Where large numbers of workers were needed—on cotton and tobacco farms in the South—slaves provided the labor. Workers were subject to the master’s whip rather than the fear of unemployment.

As industry grew in the North, a continuous stream of labor was attracted and actively recruited from abroad. Each new wave of immigrants entering the reserve army of labor—the Irish in the 1850s, the Chinese in the western states in the 1870s, the Italians and Eastern Europeans of the early 1900s, and the “undocumented” Latin Americans of the last half century—served simultaneously to put the fear of unemployment in existing workers and to distort consciousness and solidarity with the poison of racism. The African Americans migrating to the North during and after the two world wars and the farmers leaving the land after the Great Depression and Second World War provided additional workers for the reserve army in the United States.

In the period immediately after the Second World War, increasing productivity coincided with increasing wages in the United States. Gains in hourly wages in manufacturing during the rapid economic growth from the 1950s to the early 1970s generally paralleled gains in productivity. However, during the era of slow growth in the 1980s and much of the 1990s, real hourly compensation stagnated while productivity increased greatly. Some of the financial gains of increased productivity go to labor only if workers fight for better pay and benefits and are successful in their struggle. With the weakened position of labor throughout much of the center of the capitalist world economy, and with workers having pitifully little power in most countries of the periphery, little of the increased income created by productivity growth now accrues to labor.

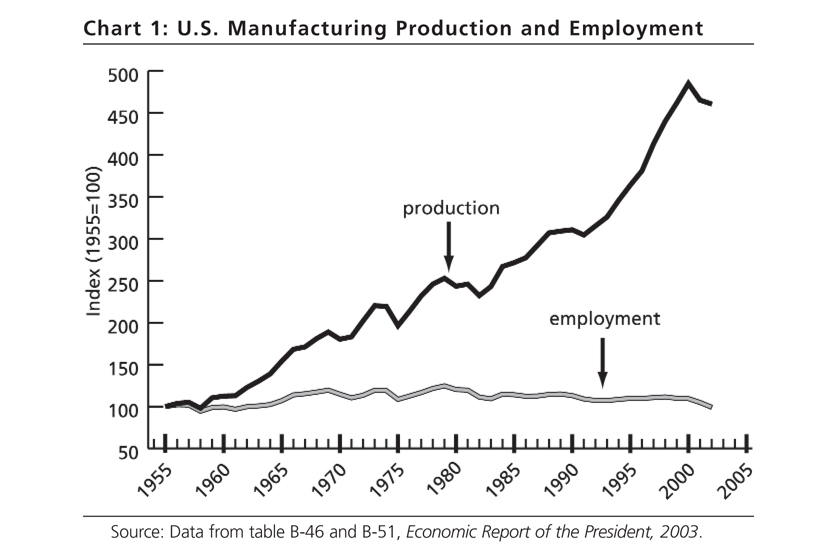

Regardless of the potential for workers to share some of the income generated by increased productivity, more efficient production creates problems for labor. With greater labor productivity—whether produced by new machines or more effective management techniques for controlling labor (“doing more with less,” as they say nowadays)—fewer or less-skilled workers are needed for a given level of output. Thus, productivity growth is a constant threat to employment security, especially with respect to well-paying jobs in mature industries in which total output is not growing rapidly. Layoffs resulting from productivity gains are, therefore, a supply source for the reserve army of labor. The increase in U.S. labor productivity in manufacturing industries has been substantial, as can be seen in chart 1. From 1955 to 2000 manufacturing production increased close to 400 percent, while employment increased by around 10 percent. While some of the increased production involved the use of components manufactured in other countries, increasing labor productivity was responsible for most of the growth in production while worker numbers barely budged.

Much has been made of the decrease in manufacturing jobs in the United States—in absolute numbers and relative to all employment. The peak manufacturing employment of 21 million workers occurred in 1979, and then decreased by about 10 percent through 2000 (as productivity increased) and another 10 percent in the 2001-2002 recession and “jobless recovery.” However, little notice has been given to the worldwide decrease in manufacturing jobs, resulting from increasing productivity and global overcapacity. A study of 20 large economies found an 11 percent decrease in manufacturing workers—some 22 million people—between 1995 and 2002 (Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2003). Decreases occurred in other core countries (Japan down by 16 percent) and in the periphery (Brazil down 20 percent). Even China had a decrease in factory workers (15 percent), as the number of people laid off from shrinking government-owned industries was larger than the number hired by the rapidly expanding export-oriented industries.

Another source of labor for the U.S. reserve army has been provided by the decrease in welfare benefits. It was clearly implied during the Reagan administration that not only were the rich not rich enough (thus the “need” to reduce their taxes so they would invest more), but the poor were not poor enough. One of the purposes of welfare “reform”—brought into reality by President Clinton—was to force those on state assistance to join the labor force and accept very unpleasant and/or low paying jobs. This stimulation of the supply of labor is undertaken while ignoring the creation of greater demand for labor—more jobs.

New features of the reserve army have arisen along with the current phase of imperialism. With greater internationalization of finance and more active flows of capital from one country to another, the fixed assets of giant corporations have spread globally. Thus, the reserve army of labor in the periphery is now more directly available to capital from the center. This has led to an increasing relative surplus population in the United States and other rich countries. As bosses seek low-cost production facilities in the periphery—directly using labor from the reserve army in those countries—workers in the center are laid off. As mentioned above, immigrant workers from the periphery, many having left rural homes, have also entered directly into the domestic reserve armies of the United States and Europe.

Workers may move from one segment of the reserve army to another, sometimes gaining employment and sometimes losing jobs, sometimes being so discouraged with the poor job market that they stop looking for work, then renewing their job search under more favorable conditions. A recent newspaper article illustrated the unpredictable changes for someone in a state of employment flux. It described a person who lost his job and looked for work for a while, then stopped looking (and was therefore no longer officially unemployed), then earned a little money through self-employment, and then got a temporary job at less pay than the original job he lost, “with no paid holidays, no sick leave, no pension plan, no health insurance, no future” (Los Angeles Times, December 29, 2003). There are, of course, many relatively secure jobs—such as those in local, state, and federal governments, and in schools. But as outsourcing of jobs and privatization of services become common and with state budgets under severe strains—even some of these jobs are growing insecure.

A Weapon of Capital

The reserve army provides many benefits to capital, principally by employing workers only when it is possible to profit from their labor. However, it is also a tool of control over labor. Having a large pool of unemployed labor ready to take the place of workers helps to keep wages from growing rapidly. However, the reality of workers knowing that they can easily lose their jobs during a recession, or if a factory moves to a lower-wage country, helps to create a docile labor force. A very large number of people have personal knowledge of how insecure their jobs really are. For example, during the three-year period from the spring of 2000 to the spring of 2003, nearly 20 percent of all U.S. workers—and close to one out of four workers earning less than $40,000 per year—were laid off from either full- or part-time jobs. On an annual basis, over 30 million jobs are lost, and roughly the same number created—a yearly turnover equivalent to about 20 percent of all jobs! Given this level of job turnover, the atmosphere of potential job loss reaches many workers who haven’t lost jobs. When family or friends become unemployed, those still employed feel insecure and are less militant.

It is also not unheard of for workers to be laid off even as new ones are being hired, a practice that keeps workers from getting too uppity. The practice of weeding out union organizers in seasonal industries is easily accomplished because the entire labor force is laid off and then rehired or replaced every year. And the workers know this—a militant leader or union organizer who makes complaints is not rehired.

The use of part-time and temporary workers—readily available because many people are not able to find full-time work—as well as the use of workers hired through contractors, are other tactics to control labor and weaken the position of full-time employees. Part-time, temporary, and contract workers are generally paid lower wages than full-time permanent workers and are not eligible for pensions, health insurance, or paid holidays. Part-time labor is not confined to the most menial jobs. It is extensively used in higher education, as universities cut labor costs by hiring more part-time “adjunct” faculty. It is also possible to hire managers, computer programmers, and a variety of specialists on a part-time and/or temporary basis.

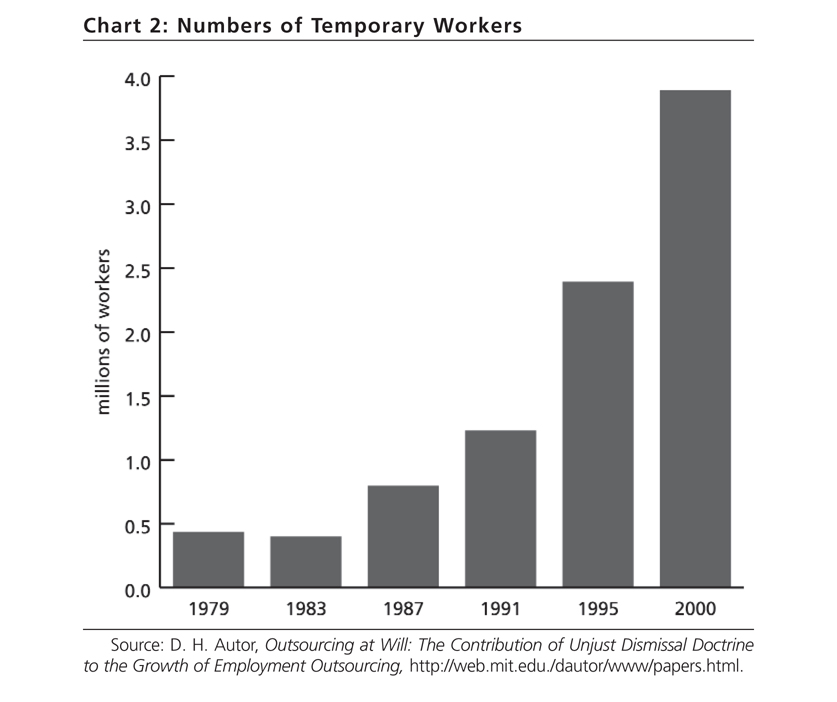

Labor supplied by temporary employment agencies is a rapidly growing segment of the labor force, now accounting for around 4 million workers, close to 3 percent of nonagricultural private sector workers (see chart 2). The increased use of temporary labor makes it easier to hire and fire workers.

Regular full-time and “permanent” jobs are a shrinking proportion of all U.S. employment, with over a quarter of all workers now working at jobs that are contingent or nonstandard—mostly part-time and temporary workers (see Ken Hudson, “The Disposable Worker,” Monthly Review, April 2001).

The use of contract labor—workers hired and paid by independent contractors who provide a workforce for businesses—puts workers in especially precarious situations and at the same time allows the ultimate employer to deny any wrongdoing in the treatment of labor. The use of contract labor is widespread, especially for agricultural labor and custodial workers. Contract laborers may work in seasonal industries or may be provided the possibility of longer-term employment. The use of contract labor to do custodial work was highlighted last fall by the raids on Wal-Mart stores, which revealed that many of the workers were working illegally (without proper documents). Wal-Mart spokespersons claimed that they were shocked to find out about the violations of a number of laws. Labor in these positions is vulnerable to the whims of the contractor, whose business is to provide a compliant, low-wage workforce. Using immigrants, working legally or not, who do not know their rights or are afraid to exercise the few rights they have, helps provide the ultimate control. Many contract laborers do not speak English, adding another layer of dependency on the contract bosses. Many of the custodial workers at Wal-Mart were not paid for all hours worked and were forced to work seven days a week, but they knew of no mechanism to obtain their full wages or days off.

Another tool for keeping labor costs low is offsite outsourcing of part of the work of a business, sometimes in cheaper nonunion areas of the country and now increasingly overseas—from fabrication of automobile parts, to assembly of goods, to answering telephone questions. This trend serves to convert a section of the workforce, which was previously employed in relatively secure (with strong union protection) and frequently well-paying jobs, into members of a lower level of the reserve army. Increasingly services are being outsourced abroad. “Overseas facilities are now handling all aspects of employee compensation, benefits, finance and even accounting—in short, any functions that are not unique to the company and are not part of its essential business” (New York Times, January 3, 2003). Outsourcing of computer programming and other white-collar work is also accelerating. The growing popularity of Web-based courses offers the opportunity to outsource even college-level teaching. A colleague of one of the authors recently took a Web-based course with two instructors—one in California and the other in Greece. This is clearly a significant threat to the jobs of teachers in higher education.2

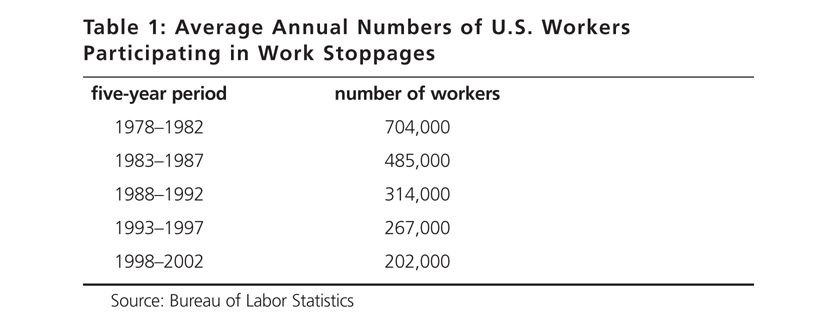

While the existence of the reserve army poses a constant threat to the livelihood of workers, the danger it poses is especially potent at this time. In the United States, a direct confrontation with organized labor began in the 1980s with the Reagan administration’s defeat of the strike by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Association (PATCO). The president ordered the firing of all the strikers, despite potentially harmful effects on the airline industry as well as air safety. This set a tone that made it acceptable once more for businesses to play rough with workers. Lax enforcement of the National Labor Relations Act, workers fearful of job loss to outsourcing at home and abroad, and the aggressive stance against labor combined to create a more docile labor force. The timidity of labor in confronting management is indicated by a marked decrease in the number of workers involved in labor stoppages (formal and informal strikes by workers as well as lockouts by employers), as indicated in table 1. During the same period, 1978-2002, the average annual worker-days lost to work stoppages declined by 65 percent, from close to 20 million to around 7 million. The consequences have been the loss of previously won benefits and a long-term stagnation of wages. Between 1973 and 2000 “the average real income of the bottom 90 percent of American taxpayers actually fell by 7 percent” (Paul Krugman, The Nation, January 5, 2004).

Given the current anti-labor atmosphere promoted by U.S. business and government—such as the tips the Labor Department gives to employers about how to get around paying overtime to low-income workers (New York Times, January 5, 2004)—it is hard to believe that the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) states the following:

[The] declared…policy of the United States…[is] encouraging the practice and procedure of collective bargaining and…protecting the exercise by workers of full freedom of association, self-organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of their employment or other mutual aid or protection.

The NLRA was passed during an exceptional time in U.S. history, when the depression brought forth an unusual constellation of forces—including capitalists who were concerned about the viability of the system and a militant labor movement. Even though the law still exists, it has been subverted repeatedly by both government and bosses.

The Reserve Army—In the Open and Hidden

Although at the top of the heap among capitalist countries, the United States has—and indeed depends on—a large reserve army of labor. While the total size of the reserve army of labor in the United States and elsewhere is difficult to determine, there is information on the status of some of its sectors. First there are the unemployed and the underemployed. At present (February 2004) in the United States, there are over 8 million people actively looking for work (defined as having looked within the last four weeks) and officially considered to be unemployed. The “official” unemployment rate declined between November 2003 and January 2004, from 5.9 to 5.6 percent but not primarily because of new jobs. With only 33,000 more people working at the end of this three-month period, the main cause for the decrease in the official unemployment figure was that over 200,000 people stopped looking for work. There are over 2 million people that want to work but have stopped looking and they are not counted among the unemployed. There are also part-time workers that want to work full-time, approximately 4 million people. The total of underutilized and not utilized workers in the United States comes to around 14 million people—about 10 percent of the potential labor force.

There are many people that don’t show up on most surveys of unemployed or underemployed. For example, the approximately 2 million U.S. prisoners are for the most part removed from productive employment. There is also evidence that some discouraged job seekers have gained disability pensions as a result of enhanced benefits and liberalized qualifications for programs for the disabled. Some workers permanently stop looking for work when faced with long periods of bleak job prospects. Downsizing companies encourage other workers to retire with the offer of early pensions or generous severance payments—over 21,000 workers at Verizon, 10 percent of its labor force, recently took financial inducements to retire (New York Times, January 11, 2004). They retire early and may receive private pensions, as well as Social Security retirement payments after reaching age 62, and therefore are not even considered “discouraged” workers. This group is not evaluated by most surveys, but an indication of its magnitude is that the proportion of U.S. men from 25 to 54 years old that say they are retired and not looking for work rose, from less than 6 percent in 1991 to over 10 percent in 2001 (Issues in Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Summary 03-03 September 2003). Germany, in an effort to reduce the embarrassingly high number of officially unemployed has made a novel offer to workers 58 and older. In return for signing a statement stating that they are no longer looking for work, they can continue to receive payments equal to unemployment benefits until eligible for a pension (Wall Street Journal, December 22, 2003). That’s quite an innovative technique for reducing the official unemployment level and making the economy look better!

Implications

The only way to maintain full employment, if it is ever reached, is to create sufficient new jobs annually to keep pace with productivity growth as well as population growth. At the current rate of population growth, a net gain of about 140,000 jobs per month, about 1.7 million per year, is needed just to keep pace with the increase in the working-age population (calculated from table B-35,Economic Report of the President, 2004). However, the normal workings of the system are such that it never delivers the number of jobs needed for full employment. In fact, governmental policies as well as the decisions of many individual capitalists and their representatives are aimed at maintaining a sufficient reserve army so that the economy runs according to the needs of business, with maximum potential for accumulation of capital.

The perpetual presence of a pool of workers—unemployed, working part-time but wanting full-time work, working in jobs that they know might be lost to outsourcing, or working in jobs that are especially sensitive to recessions—is essential to the laws of motion of capital. It constitutes the most important prerequisite for capital accumulation and is central to the difficult conditions of workers in societies dominated by capital.

The fear of losing one’s job helps to create and maintain a docile workforce and contributes to racism and anti-immigrant sentiments. When there aren’t sufficient jobs for all, competition for employment can take the form of antagonism against a minority population. The reserve army serves to maintain a downward pressure on wages and to increase job insecurity, making it harder for workers to fight back.

It is hard to organize unions in an environment where there is always surplus labor that can not only replace militant leaders but also an entire labor force, if necessary to break a strike. Workers in many businesses are well aware that if they get too bold and demand wage increases or resist concessions the response from owners will be to move the plant to Mexico or China. Thus, in addition to a mostly hostile government and media attitude toward labor for the last few decades, the fear of job loss has had a profoundly quieting effect on militancy. Union membership in the United States has declined markedly over the last two decades and now represents only 13 percent of wage and salary workers.

A reserve army makes an extensive welfare system necessary. Because workers have only one way to live under capitalism—by selling their labor power—a reserve army necessitates some mechanisms for maintaining the unemployed and those earning poverty wages in a state in which they are available and ready to work when capital calls. From the capitalist’s point of view, the government should maintain a minimal unemployment and welfare system so that it uses as little as possible of their corporate money and taxes. Of course, it is also to capital’s advantage to diffuse the costs of the welfare programs, with as much funding as possible coming from charitable donations or the workers themselves. Popular struggles may gain successes, such as the Great Society welfare programs of the 1960s, but, when conditions are favorable for reversing these gains (as they have been in recent decades), capital is ready to reduce or eliminate social programs.

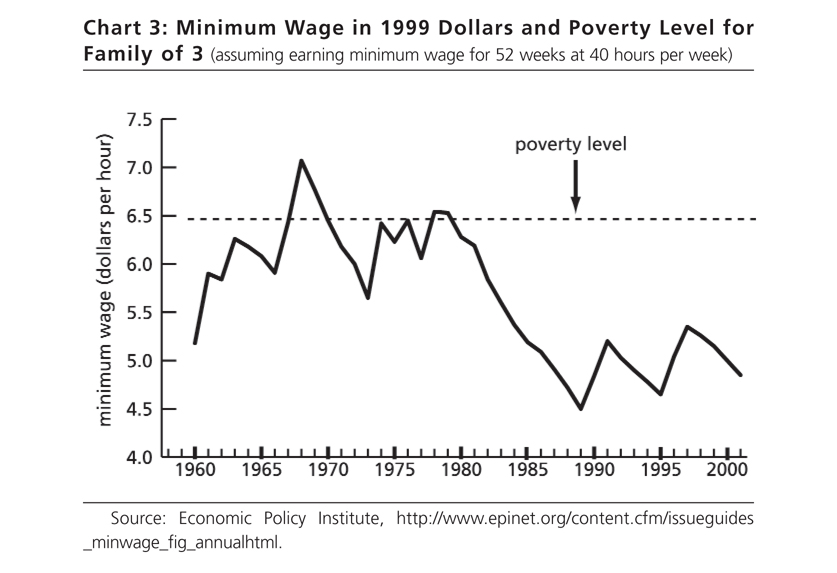

Persons in the lower reaches of the reserve army naturally and through no fault of their own require assistance to maintain themselves—unemployment benefits, government supported welfare, privately donated food, and so on. Even those employed part-time or in low-wage full-time jobs need help to pay for rent, utilities, food, and childcare. The federal minimum wage, currently earned by nearly 7 million workers and influencing the pay of millions more low-wage earners, hasn’t kept pace with inflation—since the late 1980s it has been about $1.50 an hour less, in constant dollars, than it was in the late 1970s (see chart 3). Once able to cover many of the basic needs of workers, the minimum wage is no longer sufficient. Someone earning the minimum wage of $5.15 per hour (current dollars), for 52 weeks at 40 hours per week, has an annual income of $10,712. This is only three-quarters of the $14,300 needed for a family of three to reach the officially defined poverty threshold.

Part of the explanation for the meager support for those consigned by the capitalist system to the reserve army of labor is an ideologically-driven notion that has taken deep root among the U.S. population. The problems of the poor, according to this view, are mainly due to their own failings—they are lazy or just haven’t had the foresight to get a good education, or had children when they were too young. This perverse logic, that an essential component of the economic system—produced and continually reproduced by capitalism—is somehow the fault of the least powerful, is also internalized by the poor themselves. Even if the myth were true, it would still be immoral to deny adequate shelter, food, and healthcare to the children of such “deficient” parents, or to the “failed” individuals themselves, for that matter. Racism also plays its part, with the misperception among many whites that welfare is a program mainly for minorities.

Because a large fraction of capital’s future needs for labor can be filled by the less educated echelons of the reserve army, an educational system in which all succeed is not necessary. The Bush administration’s intrusion into public school education (the so-called No Child Left Behind act), is no less than a blow against public education in the guise of assisting schools.

The Future of the Reserve Army

The reserve labor armies of the United States and Europe have been in a privileged position relative to their counterparts in the third world, where the greater part of the global reserve army of labor is now located. This has been the result of historic and frequently bitter labor battles fought in the core countries many decades ago. Their outcomes were better working conditions, steadily increasing wages (and a minimum wage, as inadequate as it might be), protections against arbitrary firing, more paid time off, better welfare programs, subsidized school lunches for children of low-income families, old-age pensions, and healthcare benefits. Some of these gains were made during periods of rapid economic growth, which provided surpluses that eased the pain of capitalists forced to pay higher wages. Additionally, during the Cold War, the atmosphere, while not pro-labor, was more amenable to meeting labor’s needs. Capital wanted labor’s support in the struggle against the Soviet Union as well as in the various hot wars, including those in Korea and Vietnam.

The current push by capital to enhance its flexibility in the center as well as the periphery is a huge threat to labor. The lack of union strength and militancy and the job losses in the United States resulting from the recent phase of stagnation and imperialism have resulted in a very docile and frightened labor force—causing concessions on working rules and benefits. Labor in Europe, where its historic gains have been more substantial, does not currently appear able to resist the negative changes to its working conditions and social programs. Labor in the periphery is generally weak compared with the forces arrayed against it and has few ways of fighting back short of outright revolt.

The current situation and trends outlined above will most likely continue to put more and more pressure on labor. Although unemployment rates will vary in response to the business cycle, the reserve army—regulating the supply and demand for labor—will continue as long as capitalism endures. Today this general law of capitalist accumulation has assumed a global field of operation, with the mass of the reserve army in the periphery and growing by leaps and bounds as more and more rural workers are forced into the vast urban slums of the third world. At the same time, there is no island of stability in the advanced capitalist countries—no labor aristocracy there that is seeing its conditions improve as a result of this global exploitation. The general difficulties for workers around the world in this era only mean that a larger proportion of the population will join the reserve army of labor, with worsening prospects.

What capital is doing, and will continue to try to do, is apparent—whatever it possibly can to enhance investment profitability. This will continue to exert downward pressure on wages, working conditions, and benefits for workers. For the last quarter-century the class struggle in the United States has been one-sided, with capital on the offensive and winning battle after battle. Although permanent security for those in (or on the brink of entering) the reserve army of labor depends on changing society, a vigorous workers struggle can score significant gains. Capital’s plan for the future is clear. The real question then becomes, what will be the response of labor?

https://monthlyreview.org/2004/04/01/disposable-workers-todays-reserve-army-of-labor/

https://monthlyreview.org/2004/04/01/disposable-workers-todays-reserve-army-of-labor/

.jpg)